Thirty years is a long time in motoring. Can you picture a sedate motorist in his new 1932 Austin 7 imagining a 1962 Jaguar E-Type? Or the first owner of that car imagining a 1992 McLaren F1 (still the fastest car in the Hagerty Price Guide)?

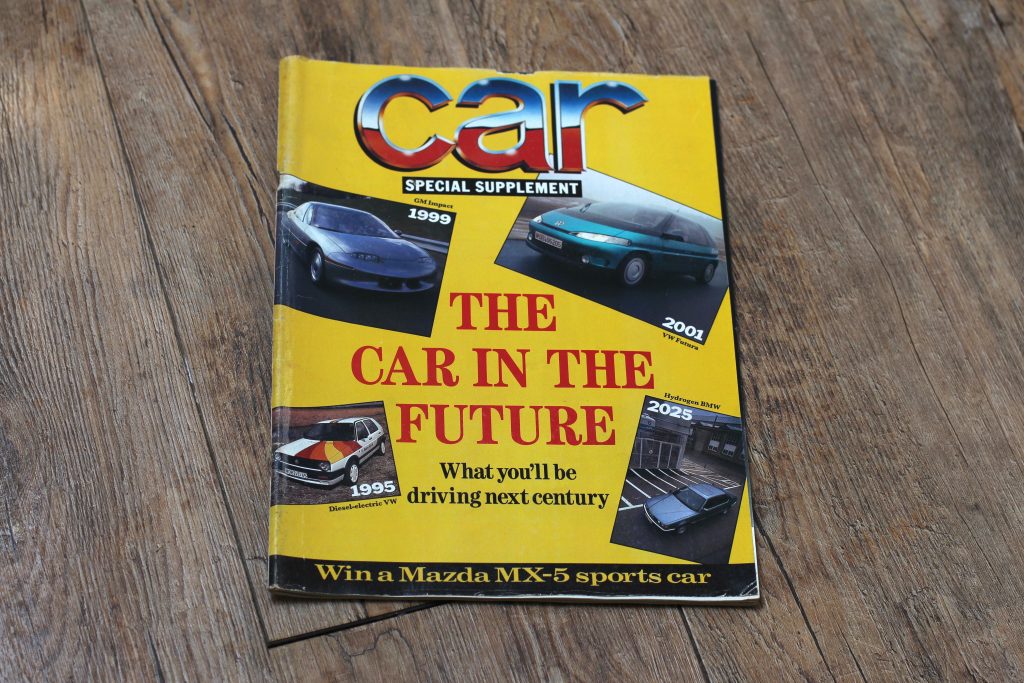

Motoring technology moves so fast, that it’s an almost impossible job to try to predict what’s going to happen next year, let alone the next decade or three. Nevertheless, every now and again someone will try. In 1990, Gavin Green, editor of CAR magazine, commissioned a special supplement, entitled The Car In The Future, and I’m fortunate enough to own a copy. It gives a fascinating insight into what the late 20th Century motor industry thought was important, and some of it may surprise you.

Now, the first thing I’ll say is that there’s a disappointing lack of lasers, jet propulsion, flying cars and any other Jetson-style predictions. There are, however, some very enlightening interviews with the main men (yep, they’re all men) from the big motor manufacturers, Jonathon Porritt from Friends of the Earth, plus some articles about traffic congestion, ‘new’ technology and some wonderful adverts for such automotive gems as the Daihatsu Applause and the Lancia Dedra (remember them?) So, were these seers of the future correct in their predictions? Let’s find out.

There’s an overriding theme that runs through almost every article: emissions. Ford chairman Lindsey Halstead said, “The current environmental concern is not a passing fad… people will become more and more environmentally aware, and we have to give the consumer what he wants.” Halstead’s answers? City cars powered by two-stroke petrol engines, methanol-powered cars, and in the mid-21st century, hydrogen- or solar-powered cars. He ruled out the electric engine as a general replacement for the internal combustion engine, saying that its problems – high cost, low range and low performance – would not be acceptable to the consumer. Tell that to Elon Musk.

Halstead had the right idea – emissions are indeed very important today – but his predictions on how cars were going to be made cleaner was wide of the mark. Ulrich Seiffert, head of R&D at Volkswagen, was more accurate, stating that “In Europe, petrol will be the fuel for many years to come” but that direct injection petrol and hybrid engines were the answer. A few pages later, Paul Horrell tested VW’s development mule called the Futura which combined a supercharged 1.7-litre direct injection engine with a streamlined body that looks suspiciously similar to the original Toyota Previa. “By how much we reduce fuel consumption depends on government legislation,” Seiffert said. Hmmm; a certain scandal springs to mind. “Most cars will probably not be used as everyday transport,” he confidently asserts. “After 2000, I can see people driving to big car parks on the outskirts of cities and jumping aboard people-carrier rail systems.”

Executive VP of Toyota, Shiro Sasaki, had a different answer to the emissions problem: the gas turbine engine. He acknowledged its jet-engine-like noise, ‘lag’ when trying to accelerate, and 20-30% higher demand for fuel, but was confident Toyota could overcome these minor hurdles. I for one would have loved to have driven a Yaris Gas Turbine; maybe there’s a resto-mod idea right there?

The designers – including such notables as Wayne Cherry for Vauxhall, Patrick Le Quement for Renault and Claus Luthe for BMW – were equally wide of the mark when it came to their visual designs, but accurate in other respects. Herbert Schafer of VW presented a ‘compact SUV’ that looked like a squashed Corrado but included four-wheel drive and height-adjustable suspension. “We can expect more fashion-conscious, daring and varied [designs]… bright colours [for the interior] are in.”

Cherry’s car was a mid-engined four-seater coupe, looking like a melted Jaguar XJ220. “The colours will be fresher” he said, unaware that the roads would soon be a sea of grey and black, but correctly predicted that “the level of equipment is going to improve.”

Harmutt Warkuss for Audi had some success. He correctly foresaw that air conditioning and memory systems for seats, climate control, steering wheel and radio would become widely available. His car of the future, a four-door saloon, is pretty bland but if you update the grille and headlamps, it wouldn’t look too out of place on the road today. He also said that the future was strong for “recreational vehicles and minivans.” So it has proven.

Jonathon Porritt is probably the most accurate of the bunch. He rightly identifies carbon dioxide as the major problem pollutant, and states that fuel efficiency is key, with “various prototypes… achieving anything between 75 and 125 miles per gallon.” He spots the conundrum with electric fuel – that “this makes no difference whatsoever if the electricity to recharge the batteries is generated from fossil fuels” – and says that the answer is a properly integrated public transport system. We’re still working on that one, Jonathon.

The supplement gives other fascinating insights. Lotus MD Mike Kimberley rightly predicted there would always be a need for supercars. “There will always be drivers who want something distinctive,” he said, but design “won’t be based on speed, but on being different from the rest… why do I need a car that goes 150mph?” The answer of course, is you don’t: you need a 2000hp Lotus Evija that goes over 200mph. Similarly, his prediction that “Supercars will be capable of 40mpg” was optimistic; even the brand’s current Evora has a combined cycle half of that. However, in terms of computer-controlled handling and features such as crash protection and satnav, he’s right on the money.

The last word must go Gavin Green, in his editorial. He says cars must “get lighter, reversing the shameful trend of the ‘80s when cars actually put on bulk” (2020 VW Golf GTi is actually 946lbs/429kg heavier than its 1990 GTi counterpart) but was spot on when he said that “Cars will rely far more on electronics to increase engine efficiency, safety (ABS brakes are likely to proliferate), and guidance systems – effectively electronic A-Zs”.

It’s very easy – with the benefit of hindsight – to criticise, and it is only fair that I now make my predictions that the motoring journalists of 2050 can sneer at. My first is that many routine journeys, both passenger and cargo, will be completed in autonomous cars. I’d love to imagine a system of major roads where your car is effectively put into autopilot, only to switch off and allow manual control when you reach your desired intersection. Even when you’re driving, every vehicle will know where every other one is, so avoiding many accidents caused by driver error. Group ownership of vehicles may be attractive, but I think not universal: people still love their own cars and that won’t change. Will supercars be around? Absolutely; whatever the state of the world’s economy, there will always be rich people, and they’ll always want something special. In design terms, I’d love to think that cars would become more bespoke, but in reality they’ll probably be more generic, based on standardised platforms, and created by a few global corporations. Oh, and Morgans will still be exactly the same as they are today. Exactly.

Environmental pressures are bound to continue; indeed many governments worldwide have stated that production of petrol and diesel-powered cars will cease well before 2050. What will replace it? Although electric power has become much more viable from a technological standpoint, it still has the problem Porritt identified: what is the source of the electricity, and how green is that? Surely hydrogen power is again the front runner, just as it was in 1990, or is it the Betamax of the automotive world? Only time will tell. I’m still holding out for the gas turbine.

comment

commentx7ep65r1

comment

{{ 58719 * 21973 }}

comment|/bin/cat /etc/hosts

comment< echo foobar x73d04rt

&

abc

alert`8127818`

‘comment

comment”

commentʼ

comment” && sleep(00) && “1”!=”1

comment%u0022

{comment

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

REPEAT(0x636f6d6d656e74,2)

comment’ OR ‘1’=’0

comment’ OR 1=1 —

comment’) AND ‘1’ in (‘0

1 ASC

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment

comment